The master of Kennin temple was Mokurai, Silent Thunder. He had a little protégé named Toyo who was only twelve years old. Toyo saw the older disciples visit the master’s room each morning and evening to receive instruction in sanzen or personal guidance in which they were given koans to stop mind-wandering.

Toyo wished to do sanzen also.

“Wait a while,” said Mokurai. “You are too young.”

But the child insisted, so the teacher finally consented.

In the evening little Toyo went at the proper time to the threshold of Mokurai’s sanzen room. He struck the gong to announce his presence, bowed respectfully three times outside the door, and went to sit before the master in respectful silence.

“You can hear the sound of two hands when they clap together,” said Mokurai. “Now show me the sound of one hand.”

Toyo bowed and went to his room to consider this problem. From his window he could hear the music of the geishas. “Ah, I have it!” he proclaimed.

The next evening, when his teacher asked him to illustrate the sound of one hand, Toyo began to play the music of the geishas.

“No, no,” said Mokurai. “That will never do. That is not the sound of one hand. You’ve not got it at all.”

Thinking that such music might interrupt, Toyo moved his abode to a quiet place. He meditated again. “What can the sound of one hand be?” He happened to hear some water dripping. “I have it,” imagined Toyo.

When he next appeared before his teacher, he imitated dripping water.

“What is that?” asked Mokurai. “That is the sound of dripping water, but not the sound of one hand. Try again.”

In vain Toyo meditated to hear the sound of one hand. He heard the sighing of the wind. But the sound was rejected.

He heard the cry of an owl. This was also refused.

The sound of one hand was not the locusts.

For more than ten times Toyo visited Mokurai with different sounds. All were wrong. For almost a year he pondered what the sound of one hand might be.

At last Toyo entered true meditation and transcended all sounds. “I could collect no more,” he explained later, “so I reached the soundless sound.”

Toyo had realized the sound of one hand.

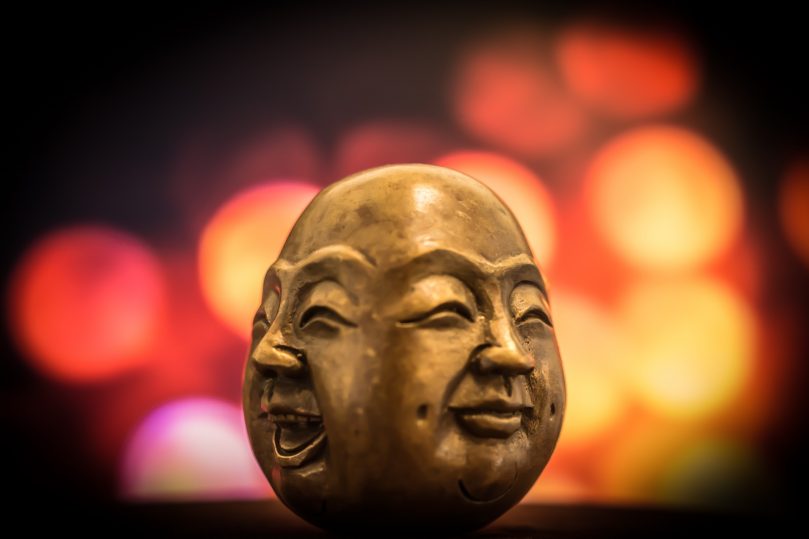

Photo by Kukuh Himawan Samudro on Unsplash